This is part 2 of an interview with Skip Groff, the man behind DC's Limp Records and Yesterday and Today record store. Part 1 is here and part 3 is here.

* * *

My comments and questions appear thus.

And Skip's replies appear like so...

Back to Limp. Why Limp?

Limp Records was based on the British label Stiff. I admired the way they had produced records, the way they had merchandised records, and the sheer volume and varieties of music they were able to put out under one collective umbrella and still maintain the ability to have hits or misses, but not let it stop them in their tracks and continue on for another day with something else really different. That's why I called myself Limp.

Where did the colored vinyl madness come from?

That goes back to working as a music director in radio. Back in the sixties, Columbia Records, for whatever reason decided to...I don't know, but somebody there...whenever a song would start creating interest in a local market, somewhere in the midwest or wherever, the national office would repress it again on colored vinyl to create interest in it, to make you notice it.

At that time your average music director, at a regular major market radio station had 150, 250 records a week landing on his desk. There were that many records coming out a week. Now there's about five, which is really pathetic, but they would press these, they were called reservices, on six, seven, eight different colors of vinyl.

We used to—at the campus radio station at the University of Maryland—we used to hang them on the Christmas tree as ornaments because they were so colorful. They were clear, translucent vinyl and there were all different shades, violet, green, red, blue, yellow.

It just looked really neat, it always impressed me, and it really made an impression on me that if I ever did anything with records, I wanted to do stuff on colored vinyl.

How did you decide what to put out, what not to put out, that kind of thing?

A lot of it had to do with who I was friendly with at any particular time and how much money there was in reserve to do stuff with. I had about 40 releases either envisioned or scheduled for release on Limp that never came out. We ended up putting about 25 or 30 out all told.

If you put a gun to my head I could probably write them all down, but...

I have a list right here.

Oh, ok ok.

A lot of people from all over the world have emailed me from time to time saying, you know, do you have a Limp discography, and what are the missing numbers and all that.

Those missing numbers confused the hell out of me for a long time too.

Well, I have pieces of paper somewhere that say what those missing numbers are supposed to be, but I've never been the most organized person in the world. I've got tons of paperwork, you know.

I have a chronological list of Limp Records releases here. I'll just name them and if you could give me your thoughts on them I'd appreciate it.

Okay.

I think that if I'd been involved with the production it would sound a little livelier than it does. It sounds kind of flat to me. The performances are good, the songs are well constructed, it just doesn't have a brightness and an edge that I thought I could have brought to it.

Dance of Days paints your first run-in with the Slickee Boys as a formative experience and describes how you wanted to work with the band from the get go. Did it really have that much of an impact on you?

Well, for me...you've got to remember, the American music scene at that point in time was in the throes of disco or, on the other side of the coin, heavy metal, and the heavy metal had become bland...star power, the kind of bands where girls would throw themselves at their feet. These guys were all miniature Mick Jaggers.

Or wanted to be.

Yeah, and Steven Tyler was the biggest of the bunch.

When I saw the Slickee Boys for the first time it brought all that great sixties garage stuff back, the British beat stuff that I liked as well as the American garage stuff, including the local garage bands. They did a lot of covers of those songs, as well as ones that you would just never hear. They had a lot of original material that fit in with the flow of it.

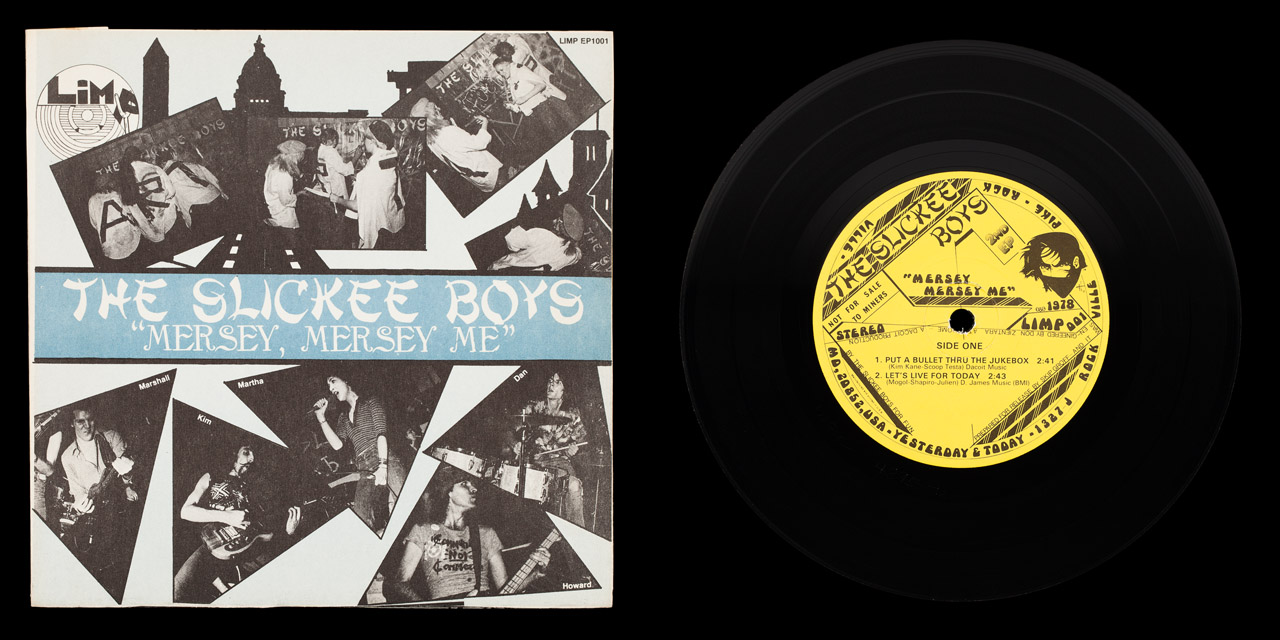

Like I said, when I first saw them they had already put out their Separated Vegetables album and the Hot and Cool EP, which had "Psychodaisies" on it—a Yardbirds B side that very few people know of because it wasn't on the American 45, it was only on the British 45—and a couple of their original songs. I just wanted to work with them. They had already prepared this next release and I put up the money to release it, press it up. It went from there.

What did you think of Dance of Days by the Marks Jenkins and Anderson?

A much better written and researched book about that era than the chump books written about the sixties DC scene. Mark Jenkins is a professional writer and a record fan.

Rudy Protrudi, who later had the Fuzztones, was good friends with the Slickee Boys, and they performed a lot locally. Both Kim Kane and I approached them after seeing a show, and we both wanted to put out a record by them, so we did it as a split release between Limp and Dacoit. Even though it sounds like it's recorded live, we didn't have anything to do with the production of that. They did that themselves.

It's rated very highly as a collectible item, perhaps undeservedly so. I think "Knocking Down Guardrails", which got put on probably the Best of Limp...I see you're...

:30 Over DC.

It is? (laughs) Is this going to be on the final test?

Yes, yes it is.

(laughs) Well in any case that was a song that they had left over from those sessions or sessions they'd done later. I thought that was a much better, representative, recorded sound of what they were.

I think that the More Than Just Good Looks EP sounds like a party record. It just sounds like it was recorded live and, obviously, "Punk Rock Janitor" is.

This is something that Howard Wuelfing produced. The Shirkers were a band that Kim Kane's younger brother Thomas was in with Libby Hatch—Mark Jenkins' girlfriend. Mark was a good friend of Howard, and he was a reviewer for several of the Washington papers at the time—still is—and he wrote the book that you referred to earlier.

Howard Wuelfing produced the record and Thomas and Libby were the only ones I knew in the group at the time. Howard brought it to me as a finished thing. He had his own label, Teen-A-Tunes, that he'd previously done some of the Nurses things on, but he wasn't really active with it. He thought that having it on Limp would give it greater selling power, greater critical edge.

I like the record a lot. "Drunk and Disorderly" had that kind of frantic B-52s inner feel, and I really thought that Suicide was a stronger cut, but "Drunk and Disorderly" has obviously become something of an anthem, and it's a very, very rare record.

Do you know anything about the production? Obviously Howard Wuelfing wasn't too happy with it since he did a remix for inclusion on the Best of Limp.

No, I remixed it.

Really?

He didn't remix it, I remixed it. That's one of the things that...

That leads to the famous story, at that same session, when I was down at Don Zientara's, I remixed one of the SOA cuts that I'd done with Henry to possibly include on the Best of Limp. When Henry heard it he pretty much threatened to kill me. He said, "What are you trying to do, ruin my career?" And this was when he hadn't even joined Black Flag! So he really felt strongly about what I'd done with it. He thought I made it too much of a top 40 type thing. That was dropped pretty quickly.

I wonder what he would feel today hearing it.

How do you think Black Market Baby's cover version compares to the original?

I know you love the Shirkers, but the BMB/Ian version knocks its dick in the butt. Can I say that?

Sure! A little cussing's good for the blood.

Did you ever see the Shirkers? I've heard that they only played once.

No, I wasn't aware that they'd ever played.

Where did you get the idea of using two 12"x12" sheets of paper instead of printed LP covers? I assume it was a cost-cutting measure, since printed sleeves are ridiculously expensive.

That's part of it, the other is that seventies bootleg albums came packaged that way and we thought it was a punk thing to do.

What made you pick the Penetrators to open up the album?

There was no question that that cut was...I mean, that was something that I would have been proud of if I had produced. It just soared and had great production from start to finish. It was definitely the thing on the album that sounded the best produced.

We wanted the sampler to be representative from A to Z, start to finish, good to bad, of what was happening in the local DC scene. So we had to balance out stuff like "Get Up And Dance" by Jeff Dahl with something like that. We wanted to get all the variants, and the things that were happening in DC at the time.

As I said, the purpose of the album was not particularly to please the artists or musicians that were on it, or to sell records locally, but to educate people in other cities and towns and across the world about what was happening in DC. Everybody was focusing on Los Angeles and New York and London and that was it. Later on it was Akron with Devo, Cleveland with Pere Ubu, and Washington, which I thought had a great scene, was not getting any attention.

Did you work with the band at all?

No, no, as far as I know they were down in Virginia.

Alexandria.

They only released two cuts, both on Limp Records, were there any plans or ideas for any more?

What was the other thing? "The Break"?

Best of Limp. "Broken Promises". "The Break" was on :30 Over DC.

"Broken Promises", see you know this better than me.

I also planned the Best of Limp Volume 2, which would have rounded up some of the other cuts. I had a lot of outtakes from the Razz and the Slickee Boys and the Nurses and things like that, as well as some leftover cuts from :30 Over DC. The Rudements, which I think were one of the better bands on :30 Over DC, gave me a whole four song EP that they never released. I still have the master tapes in my basement.

I guess I had forgotten that the Penetrators were on there. Nobody will put that one on CD, so...

Who was Don How—

David, David Howcroft.

Why do I have Don Howland written down? Anyway, who was David Howcroft, who wrote the :30 Over DC liner notes?

I told you about Steve Lorber having a show on WGTB. David Howcroft had a show on WGTB as well. David's show was oriented more towards the current new wave stuff, the bands coming out of—and you've got to remember this is all brand new at this time—the bands coming out of New York, the B-52s, and local bands like Urban Verbs—the more progressive end of things.

Steve would occasionally play some of the British stuff, but he was more into the sixties psychedelic and punk rock stuff and that was the basic thrust of his show. So when it came time to start getting interest and putting together the album to showcase the DC scene, David's show was much more of a place for that kind of thing, and he had contacts. I had contacts through the store. My friend Howie Horowitz from the Music Machine up in Baltimore had contacts with Jad and David Fair from Half Japanese, who hadn't even recorded yet, but were regular customers at his store, buying the new releases and things. That's how he ended up writing that for :30 Over DC.

And the CD?

Well, I'm certainly happy with the way the cover looks on the new thing. I think Henry did a great job with that. I love pastel colors. Kim Kane's artwork was always great but it felt like a watercolor waiting to be painted, especially with the way we had the stars with all the groups, so the way Henry did it was just perfect.

It took ten years to get the CD put out. He started working on the release, getting permission from all the group members, and then Jim Kowalski from White Boy got arrested and went to jail for life, so he was gonna drop the project. For two or three years it sat there, and then Dischord encouraged him to go ahead and do it. He picked it back up again and had to go back and get all the permissions from everybody.

The last few months before it came out I had to help out with his office manager and contact a lot of people and get their publishing affiliations and things of that nature. I didn't get any money off the record then or now.

I had nothing to do with that. If you ask the group today they'll say I bootlegged it. The fact of the matter is that they were friends of Kim Kane, and Kenne Highland was one of the two main guys in the group, the other was Ken Kaiser. Kenne Highland was stationed in the army down here, but the Slickee Boys had known him from when he was in a punk band up in Boston. He used to come into the store—at the time I think he was stationed at Fort Meade—and he and Martin hooked up for the release of that thing, and Martha and Howard were on it.

Keith Campbell was on it too.

I didn't know that.

I had nothing to do with it. All I did was set them up with my pressing plant and gave them the logos to put on it. I'm pretty sure it's on blue vinyl.

They released it, not me. I just gave them the name. They begged me for the name, because again, like the Shirkers, they wanted...at that point Limp had the Slickee Boys out, and had the Shirkers, and Razz out and the :30 Over DC album and they wanted some kind of recognition.

A year or two ago, when Gulcher were talking about reissuing it I called them up, I emailed the owner, and asked them what the story on it was. They said, you bootlegged it, you don't deserve anything. Ken Kaiser says you never had any rights to release this thing.

The Reind Dears were another Howard Wuelfing production, and again, he was working at the store at that point. His marriage was falling apart and he was falling in love, at least in his mind, with Diana Quinn from Tru Fax and the Insaniacs and wanted to do a project with her. That was the sole reason for that record coming out.

It's had a staying power in terms of interest for the collectors that I would never have predicted, and if I ever find where the rest of those picture sleeves are—I gave you one—I'll certainly let you know.

You got a test pressing of that from me, didn't you?

Yeah, the rejected test press.

It's a very rare item. I don't know why it was rejected.

They omitted the count-in on the B side, that's the only difference.

I'd known Martha from the Slickee Boys and when her new band was ready to do something they approached me because there were really only two labels at that time in DC, my label, and there was Wasp Records, Bill Asp's label over in Virginia.

We were like two camps on opposite sides of the river—you're either with us or against us. The bands on his label shopped at my store, the bands on my label shopped at his store, but he and I didn't see eye to eye. We both had different perspectives on how to do things. He wanted to put out records and make money, and I didn't care if I made money as long as the records got attention for the groups.

I think Airtime was one of the greatest records ever to come out of DC. I edited it. That was my entire involvement in it, aside from putting it out.

They had done a concert for DC101 live from a local venue, and I'm sure there's more songs than those four, but I have not been able to find where they might be. In any case, at some point I had access to the whole tape and took it over to Zientara's and chose those cuts and put them in—they weren't together in the concert the way they were on the record, they didn't necessarily fall together.

I thought it was a really, really strong EP, and it showed their dynamics and versatility on stage, the ability of Michael Reidy to go from a ballad to a harmony type thing to a hard rocking type thing. It also showcased Tommy Keene's "Love is Love", which at that point in time was developing into the Razz's real tour de force. It became the ending piece later on, and they would do that at the very end of a set and expand on it.

When did you run into the band, and what was your impression of them?

I saw them once when Abaad Behram was the guitarist (later of Johnny Bombay and the Reactions). Then, after :30 Over DC, which they didn't want to be on, Ted started hanging around the store. After Tommy Keene joined, I was going to see them two or three times a week—I wasn't married then. The Varsity Grill in College Park was the best place to see them, but they played everywhere in town. As I mentioned in an email, they were just incredible showmen live: Funny, as well as masterful lead singer, two lead guitarists, tight rhythm section, and an incredible mixture of originals and covers, with shows varying greatly in terms of content from one night to next.

All points considered, they were the best DC rock band ever.

They produced those tracks themselves at Track, and I had nothing to do with it other than putting the record out. They just came to me with that because I had put out the Airtime EP and they all liked the way that went.

I have a picture of them, in my files, of them at Peaches the day the 45 came out. Peaches used to be over on Nicholson Lane, and all the members of the Razz were there holding up the EP in front of the cassette rack there.

Continute to Part III

See more: all posts from this week, summary posts from this month, Music, Writing.